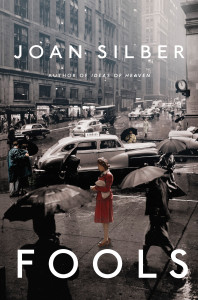

Joan Silber is a celebrated author who has received acclaim for her work as a novelist and a short story writer. Her short fiction has been chosen for an O. Henry Prize three times, twice for a Pushcart Prize, and once for Best American Short Stories. She has been a recipient of an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Guggenheim Fellowship, grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York Foundation for the Arts, and it should come as no surprise that her first novel, Household Words, won the PEN/Hemingway Award. Among her other books, Fools was on the Long List for the National Book Award and was nominated for the PEN/Faulkner Award, Ideas of Heaven: A Ring of Stories was a finalist for the National Book Award and the Story Prize, and The Size of the World was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Prize in Fiction, and was one of Seattle Times’ ten best books of fiction of 2008. Her other works of fiction include In the City, In My Other Life, Lucky Us, and her non-fiction work from Graywolf Press is part of “The Art of” series, The Art of Time in Fiction.

Her short stories have appeared in The New Yorker, Tin House, Ploughshares, The Paris Review, Epoch, Agni, and Northwestern Review.

She is currently teaching at Sarah Lawrence College and Warren Wilson College. She has also taught at New York University, the University of Utah, Boston University, and the 92nd Street Y. Her summers have included teaching and conferences at Napa Valley, Bread Loaf, Indiana University, Manhattanville College, Stonecoast, Aspen, and Sarah Lawrence College.

Christine Otis: I really enjoy your work. Your stories remind me of older work like Anton Chekhov, Alice Munro, Eudora Welty, and Edith Wharton. There is a slow methodical pacing to your stories, with a reveal, and it’s the pacing that draws the reader into the story. How do you manage that type of pacing?

Joan Silber: Thank you. I think this pretty much comes naturally to me. I don’t think of it as slow pacing. When I read novels now it seems to me they linger more exhaustively in certain scenes than I do.

I’m still more of a short story writer—I move around somewhat quickly; I cover a lot of time in a short space—so the slower pace you’re feeling may be within the scenes. That gives a different sense of event.

I think if you’re always writing about people you like, and approve of, I think that’s a weak position for a fiction writer to be in—you want your characters to get into trouble, and do stupid things.

Otis: So would you say, for you, it is the character development that comes first, or the plot? Or do they go hand in hand?

Silber: I usually have a situation roughly in mind. The best example I can give is in Ideas of Heaven. I decided I wanted to do another story from the viewpoint of the mean dancing teacher from the first story, “My Shape.” I knew who he was to Alice, the main character, but I wanted to know who he was to himself—this became the second story, “The High Road.” I knew the story was going to have to move toward an episode more significant to him than she ever was. Once I had characters he was in love with at points in the story, it began to find its shape.

Otis: Is that true for a lot of characters in your stories, to have the story shaped around love?

Silber: For me, that’s one of the highest topics definitely. Not always, but it’s in the story somewhere.

Otis: With Rhoda in Household Words, you stated you didn’t particularly like her; I’m referring to what was written in the back of the book. Is it difficult to write characters you don’t like?

Silber: I don’t think I would have put it that way.

Otis: Okay, how would you put it?

Silber: I wouldn’t say I disliked her, my intention was to get inside her head, which requires sympathy. I think if you’re always writing about people you like, and approve of, I think that’s a weak position for a fiction writer to be in—you want your characters to get into trouble, and do stupid things.I learned from Chekhov—Chekhov is wonderful at presenting characters we don’t like initially, but we become so intimate with them, we do like them in time.

Otis: So is there a difference between writing characters you have more sympathy with than others; if you like a character is there a different way you approach that character than one you’re not so fond of?

Silber: I learned from Chekhov—Chekhov is wonderful at presenting characters we don’t like initially, but we become so intimate with them, we do like them in time. Sometimes he pulls back at the end of the story and reminds us why we didn’t like the character in the first place. This doesn’t always happen, but I’m interested in that.

In the story about missionaries in Ideas of Heaven, the main character, Liz, was based on letters I read in my research. I used Eva Jane Price’s China Journal, 1889-1900. I wanted to be in sympathy with the missionaries. They go thousands of miles to this strange place and try to spread their own religion and culture—which would certainly not be my way (I’m not even Christian). A 21st century person can knock such people, but I didn’t want to do that; I wanted to get under her in some way.

As a child, I spent a lot of time reading Louise May Alcott, and I knew the logic of her thinking, which helped me here. I wanted to go outside clichés about someone like Liz. When I teach, I tell the students it’s not the job of literature to tell people what they already know. What they already know is received opinion, the agreed-upon assumptions of their time and place.

Otis: When you write your characters, do you inhabit them when you’re writing, or are you separate from them when you write?

Silber: Both, I think. I try very much to be with them; I do a very close point of view. My central characters, I’m pretty much inside of, but I do see them separately. They aren’t me.

Otis: How much time does it take for you to design your characters in your stories?

Silber: It varies, but it’s never fast. I would say I spend maybe three months on a story, or longer.

Otis: How much research do you put into your stories? When do you know when to actually stop the research to do writing, or do you do the writing and the research at the same time?

Silber: I do a lot of research first to get me going, and also I’m looking stuff up as I’m working. In the early stages, I might read books, then I’m working and going online checking stuff.

Otis: How do you not get bogged down in the research aspect?

Silber: I like getting bogged down.

Otis: When do you know when to pull away from the research?

Silber: You don’t entirely know what the piece is about when you start it, and that’s when it’s confusing. Once you have it [your story] more focused, what emotions you want the story to carry, then it is easier to figure out what you want to use.

Otis: Would you say you have your idea first before you do your research? Or are you reading, and you stumble upon something that triggers an idea?

Silber: Both. For the missionary story, I was about to take a trip to China, and one of my friends gave me a book by Jonathan Spence, one of the American experts on China. It was accounts of various foreigners who went to China from Marco Polo on. In that book, there was a chapter on missionary wives. The last book I wrote, Fools, begins with a story about anarchists in the 1920s and uses the real-life character of Dorothy Day, an extraordinary woman who helped found the Catholic Worker, a movement that set up houses for the homeless and had its own radical newspaper.

I was already writing stories about romantic love, and religious feelings and how they cross each other. While I wrote “Ideas of Heaven,” I kept looking up things about China.

Otis: Did you eventually visit China?

Silber: Yes. While I was there, I was in a city called Luoyang, and early in the morning you can watch people practice martial arts. (They also do this where I live now—I live near Chinatown in Lower Manhattan.) While I was standing around there, some guy came up to me—an old guy—who wanted to practice his English, and had English students, and it turned out when he heard I was a professor, he asked me if I’d heard of Oberlin College. The missionaries I was working on were from Oberlin! I gave the college another name in the story I wrote, but he had been one of their students from the 1930s. It was a great coincidence and he referred me to a classmate in America, who was with him in China at that time, who was able to direct me toward some research sources. It was very helpful.

Otis: Have coincidences like this happen to you before?

Silber: The last book I wrote, Fools, begins with a story about anarchists in the 1920s and uses the real-life character of Dorothy Day, an extraordinary woman who helped found the Catholic Worker, a movement that set up houses for the homeless and had its own radical newspaper. I was interested in the earlier phase of her life when a pregnancy led her to religion, and in reading about her I discovered that the father of her child (also an anarchist) was related to an old friend of mine! My friend Elspeth did remember him—quite fondly—and gave me a wonderful sense of him, which I used in the story.

Otis: How do you weave your stories with your characters, so you get to see a broader spectrum of how one life affects another? Are you purposely making those decisions before you begin, or is it more organic?

Silber: One way stories get linked is to take a minor character from an earlier story and make him or her the major character of another story. I love the irony—this person you’ve totally forgotten about comes in later.

There is a wonderful Chekhov story called “Anna on the Neck”—a young girl comes from a family where the father drinks too much and wastes all their money, so the women of the town marry the girl off to a stuffy older guy who has money. She doesn’t like him. Through a sequence of events, she takes up with other, more glamorous men, and her life is freer and more luxurious.

At the very end of the story, her father reappears again on the edges of the story, and you’ve forgotten all about him. It’s a wonderful moment in the story. The father is drunk, and he’s trying to wave to her while she’s in a fancy carriage, and her brothers are trying to hold him back from doing that. I loved that. I love the effect it had on me, so I wanted to get that sense that what you’ve forgotten about comes back into the story again. I’m looking to do that; I’m trying to find the way to do that.

Otis: So how do you do it?

Silber: Sometimes I know ahead of time of how I want to bring that character in again, and sometimes it occurs to me as I’m working.

Otis: In The Size of the World, how did you come to focus on the defective screw as a focal point of the story that brings all of your characters together?

Silber: That one, the first story, which takes place in Vietnam, is based mostly on my brother. He was an engineer, who was in Vietnam, sent to trouble-shoot problems with guidance systems.

We’ve always had historical novels, but not so much historical short fiction. Andrea Barrett was a great pioneer of that about 20 years ago.

Otis: So the defective screw part was just something you came up with because your brother was an engineer in Vietnam?

Silber: Yes, I made that up. My brother was investigating why the navigation systems were going off course—I don’t know what he found out. I knew, of course, that Bangkok was used for R & R [Rest & Relaxation, or Rest & Recovery] by U.S. soldiers. I had traveled to Thailand, and really loved it, so I wanted to use it in some way. And later in the book I was able draw on different accounts of 19th century travelers in Thailand.

When I’m linking stories, I make them up as I go along—the great thing about the form is that one story can give rise to another.

Otis: What made you decide to write about AIDS in Lucky Us?

Silber: I was working as a volunteer for Gay Men’s Health Crisis, so I was close to the epidemic in the years I wrote the novel (2001).

Otis: How do you decide to write about a specific era? Are you drawn to certain eras and feel compelled to write about them, or do you fall into it?

Silber: I’ve always loved history. Among other things, it gives you a sense that now is not the whole story. Our own era is always a very incomplete picture of how humans live.

We’ve always had historical novels, but not so much historical short fiction. Andrea Barrett was a great pioneer of that about 20 years ago.

Otis: Would you say historical fiction is your favorite thing to write?

Silber: No, I love it, but it’s not an exclusive love.

Otis: What are other things do you love to write about?

Silber: I do love to write about romantic love and longing, and I’m still very interested in religious feelings and ideas. We don’t have much of a language for religious feelings, outside the traditional vocabulary of institutions.

Please check back next week for the continuation of my interview with Joan Silber where she discusses novel writing, the importance of a story’s ending, fellowships, and the writers who influenced her work.